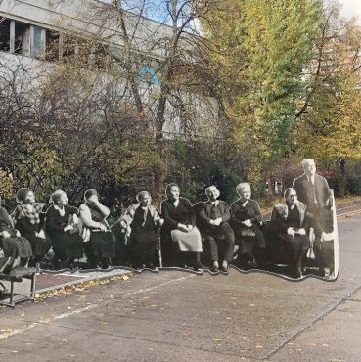

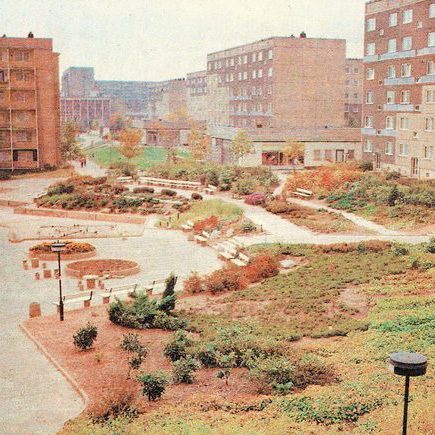

Seating furniture from the GDR that remain in public space reflect a different conception of the city – one in which furnishing followed not the principle of individual appropriation but that of collective availability. At the same time, the light, movable chairs allowed for flexible use: they could be shifted, grouped, or placed apart. Their particular quality lay in this ambivalence between collective order and personal freedom. Their standardised yet resilient presence points to an infrastructural mode of thinking that is increasingly disappearing from today’s urban landscape.